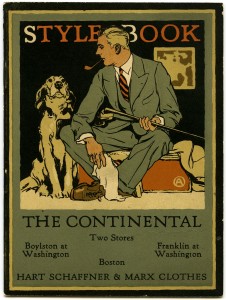

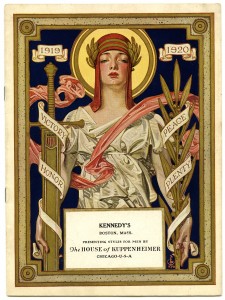

For those who can’t get enough of Gatsby fashion, RULA Special Collections recently acquired a small donation of 1910s- and 20s-era stylebooks from American clothiers Hart, Schaffner & Marx and The House of Kuppenheimer.

The companies date back to the late nineteenth-century. Hart, Schaffner & Marx began operations as Harry Hart & Bro. in 1872, when brothers Harry and Max Hart opened a small men’s clothing outlet in Chicago. By 1887, the company had undergone two name changes and a series of new partnership agreements but settled on the name Hart, Schaffner & Marx. It was soon the largest manufacturer of men’s clothing in America, selling nearly $1 million worth of clothing annually.[1]

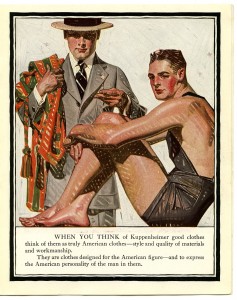

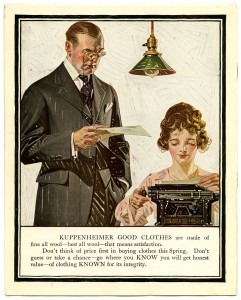

The company’s rival, The House of Kuppenheimer, was also based in Chicago. Established by Bernard Kuppenheimer in 1876, the company reached sales of $1 million per year by the 1880s. By the 1910s, it employed nearly 2000 workers.[2]

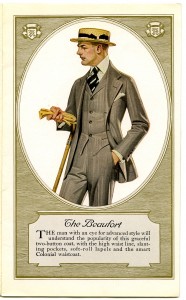

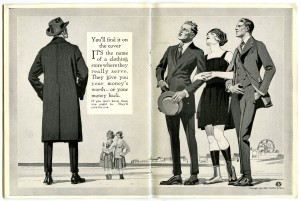

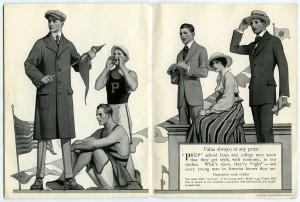

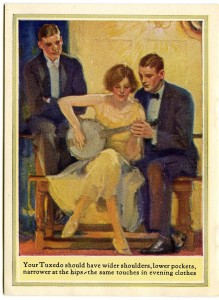

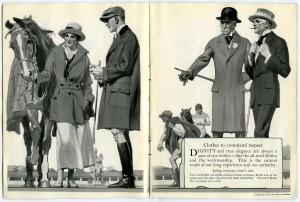

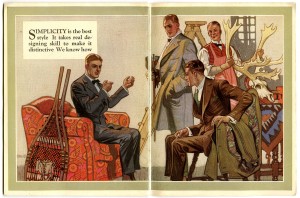

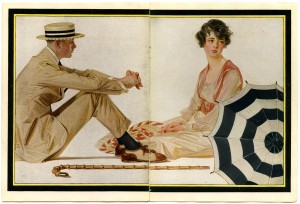

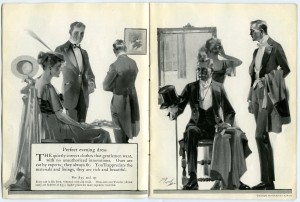

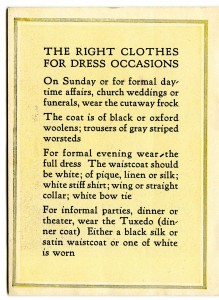

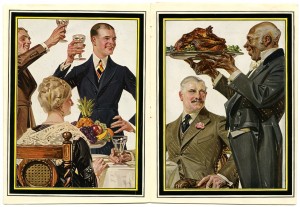

The companies specialized in tailored clothing for men, young men, and boys and distributed their catalogs through the retailers that sold their products. These catalogs capitalized on the allure of the wealthy American elite as the companies hired well-known illustrators[3] to create images that associated the brands with the fulfillment of the American dream. Taglines referring to “prep school boys” and “stylish business men” accompanied images of young men and women hunting, horseback riding, attending lavish banquets and performing other activities associated with America’s burgeoning leisure class.

Yet, much like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s iconic literary portrait of the era, the catalogs also reveal the tensions underlying the pursuit of this elusive lifestyle. Indeed, the catalogs’ subjects are, like Gatsby himself, often as remarkable for their gaiety as for their unshakeable ennui. Meanwhile, the catalogs’ recurring concern with ‘rightness’ and ‘correctness’ betrays the intense pressures of conformity that governed the American upper classes.

Despite the catalogs’ glamourous subject matter, their emphasis on value and economy additionally reveals a target consumer more likely to pinch pennies and aspire to upward social mobility than to enjoy the breeze from an already-purchased yacht. In their most disconcerting form, the images flatly expose the American dream as a reality accessible to only a precious few in terms of race and gender.

The catalogs thus stand as a rich resource not only for those interested in the history of fashion, graphic design, or advertising, but also for anyone exploring race, class, and gender politics in America in the 1910s and 20s. Stop by Ryerson Special Collections on the 4th floor of the library to see these small but powerful documents of American history (call numbers: TT620.K87 1916-1921 ; TT620.H36 1911-1925) and to peruse other resources related to the history of fashion in North America, Europe and elsewhere.

Bibliography